This is an excerpt from the book The Power of Conferences – Stories of serendipity, innovation and driving social change, supported and co-funded by Business Events Sydney. The ten stories in the book demonstrate that conferences are shared social contexts which take people away from their established routines. Within this social context, knowledge and ideas are shared and common goals are developed through such interactions. It is not surprising then that these stories demonstrate a direct connection between the staging of conferences and an extensive range of benefits and outcomes beyond the tourism spend.

The heritage now developed by stories like them in the book, is not only beneficial for personal growth but also improves, for example, the meeting and event industry, universities, cities, regions, and countries as a whole. Through business events that work with obligations, engagement and legacy in a sustainable way, we all contribute to a better world.

Business Events Sydney’s long research partnership with the University of Technology Sydney has shown that conferences deliver knowledge, innovation and best practice. However, the full legacy of an international conference can often only be measured years after that event has taken place.

There will always be a short-term boost to the visitor economy of the host city, but it’s often the longer term (or ‘long tail’) benefits, beyond tourism, that increase the overall value of the event long after it has finished. That’s because research shared, innovations explored and connections made are often just the initial catalyst for breakthroughs and global collaborations that come to fruition years later. That was the case for the individuals profiled in the book for whom conferences have played a seminal role in the development and evolution of their achievements.

When Business Events Sydney partners with organisations bidding to bring their international event to Sydney, we ask what their long-term ambition is. What does success look like for their organisation 5–10 years down the line?

Having that clear vision of how a conference can help to achieve a wider objective is invaluable and provides a framework with which to measure the impact on a much wider scale than just delegate numbers or direct expenditure.

Yet, sometimes the most important and exciting legacies come from unexpected encounters – the ones that lead to unlikely collaborations or opportunities to take research from one field and apply it to a totally different area.

At other times genuine progress is made simply by bringing people with a common cause together and uniting them behind a clear and compelling purpose; whether to accelerate a cure for disease, raise money for a particular cause, or secure greater profile and support for a campaign to create real and lasting social change.

With the internet providing a wealth of information at people’s fingertips and bringing communities together remotely, and technology constantly advancing research capabilities, we are often asked “Will conferences ever become obsolete?” The experts in this book unanimously agree that there is still no substitute for the power of congregation. They believe conferences have a bright future, and so do we.

“Whether you organise, attend or support conferences, we hope that the book and the stories in it will inspire you to think big and give you the courage and passion to use these events to help drive social change and create a lasting legacy,” says Lyn Lewis-Smith, CEO, Business Events Sydney.

“We wanted these stories and an understanding of the power of conferences to be accessible”

Introduction

A chance encounter at a conference sets up a series of unfolding events. In 1982, immunologist Ian Frazer attended his first international gastroenterology conference in Canberra, Australia. After his presentation on genital warts, a colleague, Dr Gabrielle Medley, discussed with him the potential link between the human papillomavirus and cancer. This meeting proved fateful, as it helped to put him on the path that would ultimately lead to the development of the HPV vaccine. This vaccine is now used across the globe, and may eradicate cervical cancer within a generation.

This book seeks to explore and understand these long-term outcomes: what we loosely refer to as the ‘long tail’ of conference impact. By doing so, we hope to add to an increasingly complex picture of the value of conferences. For, despite the costs and effort involved in hosting and attending conferences, despite all the online communication options for the circulation of knowledge and commentary, many thousands of events, involving many thousands of people coming together, take place around the world each year. What makes them so worthwhile? How can we plan and design conferences to allow for the full range of potential benefits and outcomes?

For the purpose of this book, a conference is defined as a formal meeting in which many people gather in order to talk about ideas or problems related to a particular topic, academic discipline or industry area. For example, the conferences referred to in the following case studies include (inter alia) medical, engineering, science and education conferences. Conferences may also be referred to as congresses, symposiums, meetings and business events; however, throughout this book we will use the term conferences.

Conference attendees usually include a mix of academics (including postgraduate students) and industry professionals, with occasional community involvement; for example, patients, careers and advocates sometimes attend medical conferences. Many conferences also feature exhibitors who may have a business or research stake in the topic area of the conference.

Most conferences are linked to a national or international professional association. Some are held in the same destination each year. However, others, like the International AIDS Conference run by the International AIDS Society, move around to different destinations, often raising global awareness of sector-related issues. Some are carefully designed to leverage particular outcomes linked to the mission of the association(s) organising the event. Others are run on a more ad hoc basis, without specific objectives other than to provide a meeting point for attendees who each have their own related but distinct agendas. Conference outcomes, then, can range from the planned to the serendipitous; from the tangible to the intangible.

Typically, conferences are evaluated in terms of their short-term impact, both individually and collectively. Individually, most conferences have some level of post-event evaluation and this is often focused around delegate satisfaction with various aspects of the event (such as venue, program, speakers). Collectively, conferences are evaluated by governments and industry, mostly in terms of their financial contribution by way of visitor expenditure. Governments are aware of the significant influx of new money that can result from hosting an international or domestic conference, and cities around the world compete to be the preferred destination site for conferences. However, there is a growing recognition that the value of conferences extends well beyond tourism and should not be measured merely by direct financial contribution (Dwyer, Mellor, Mistilis & Mules 2000).

In this book, they argue that new money, attractive as it is, is just one of the contributions that a conference can make to individuals, industry, government agencies and the wider destination community. The primary audience for this book are those who work in the conference industry, educators and students who will go on to work in this field.

“The full legacy of an international conference can often only be measured years after that event has taken place”

Re-thinking The Value of Conferences

A number of studies have pointed to a lack of recognition of the full value of conferences in traditional evaluations (Carlsen, Getz & Soutar 2001; Wood 2009; Foley, Edwards, Schlenker & Lewis-Smith 2013). As such, there is a clear need to consider conferences in more sophisticated ways that take us beyond traditional short-term economic impact measures (Pickernell, O’Sullivan, Senyard & Keast 2007). Evaluating conferences without taking account of the wider and longer-term benefits seriously underestimates their value to all stakeholders.

Previous research (Jago & Deery 2010; Teulan 2010) has identified a number of opportunities that conferences can provide, including knowledge expansion, community outcomes, innovative and collaborative projects, international relations, trade and networking opportunities, education, and enhanced business-to-business relationships. Similarly, industry reports (such as those produced by The Business Events Industry Strategy Group 2008), which have offered evidence-based examples of the economic benefits that conferences can bring, have also noted their potential to “promote and showcase Australian expertise and innovation to the world and attract global leaders and investment decision makers … to Australia.”

A peer-reviewed academic Australian study sought to examine the broader legacies of conferences (Foley, Edwards, Schlenker & Lewis-Smith 2013; Foley, Schlenker & Edwards 2010). Drawing on a range of conferences from across industry sectors, the authors collected data using in-depth interviews and secondary data analysis (Edwards, Foley & Schlenker 2011; Foley, Edwards & Hergesell, 2016; Foley, Edwards, Hergesell & Schlenker 2014; Foley, Edwards & Schlenker, 2014; Foley, Schlenker & Edwards 2010; Foley, Schlenker, Edwards & Lewis-Smith 2013). Through the analysis, six core themes emerged, reflecting the benefits and outcomes that can arise from conferences: (a) knowledge expansion, (b) networking, (c) relationships and collaboration, (d) fundraising and future research capacity, (e) raising awareness and profiling, and (f) showcasing and destination reputation.

Within these core themes, it was argued that there were more than 45 possible benefits, tangible and intangible, including the exchange of ideas, building of professional reputation, and strengthening of relationship bonds and resource ties. Application of new techniques and technologies, improved skills, and relocation to the conference destination to live and work were among the tangible benefits.

Through this and subsequent research, our studies identified a ‘long tail’ effect (Edwards, Foley & Schlenker 2011): participants reported that not only were the benefits and outcomes felt during the conference or within 12 months following the conference, they were also experiencing the benefits three to five years after the conference. Some added that the benefits and outcomes were still to be realised. These findings suggested to us that more needed to be known about the benefits and outcomes that occurred well after the conference had finished and that we needed to understand the quality of the impact, to understand the full value of conferences.

The idea of the long tail was popularised by Chris Anderson (2004) to explain an anomaly in the music industry. He noticed that infinite shelf space in the form of the internet, combined with real-time information, led to sales that collectively grew to become a large share of total sales (Brynjolfsson, Hu & Simester 2011). Such was its importance that Zhu, Song, Ni, Ren and Li (2016) suggested that the long tail was itself a new market.

According to Anderson (2004), the long tail describes a frequency distribution pattern in which the number of events in the tail is greater than the number of events in the immediate high-frequency area.

In the context of our research on conference impact and evaluation, the idea of the long tail presented us with a novel way to conceptualise and capture those outcomes that come to fruition years, and even decades, after the event has taken place. We asked ourselves: how can we measure the long tail? This was a slippery problem, and after much consideration we realised that a qualitative approach to data collection was going to be more meaningful than a quantifiable measurement approach.

“Sometimes the most important and exciting legacies come from unexpected encounters”

Conferences: Providing ‘Out of The Ordinary’ Experiences

The treadmill of daily existence in contemporary societies has been identified as a less than ideal environment for forming meaningful relationships, sharing knowledge or stopping to think with the people around us (McDonald, Wearing & Ponting 2008). Busy people often find it difficult to let go of their ‘to do’ lists for the sake of spending time with companions (Foley 2017). However, in order for meaningful social interactions to occur, ‘out of the ordinary’ opportunities are needed to encourage people to take time out from their busy schedules and established routines.

A conference is one such ‘out of the ordinary’ experience that gives attendees a break from everyday demands and facilitates shared social contexts (Small, Harris, Wilson & Ateljevic 2011) which are conducive to knowledge sharing. Such experiences provide opportunities for delegates to become part of a network of lifelong professional and personal friends – a network which can increase exponentially over time (Hickson 2006); they provide a temporal context for intensified knowledge exchange and social interaction (Maskell, Bathelt & Malmberg 2005); and they offer the chance to build relationships with other regular participants, which can result in improved performance (Bahlmann, Huysman, Elfring & Groenewegen 2009).

Conferences also provide unique opportunities to showcase, construct and brainstorm new ideas, strategies and technologies. Face-to-face communication and live presentations at such events can create a special impetus for developing new professional relationships and research collaborations. Bathelt, Malmberg and Maskell (2004) suggest that innovation, knowledge creation and learning are all best understood when seen as the result of interactive processes where people possessing different types of knowledge and competencies come together to exchange information. Such exchanges and interactions can occur in different ways, including via social media or video conferencing, but the camaraderie and sense of community that can develop around conferences, the appeal of engaging face-to-face with peers, and the relationships that are developed and enhanced contribute to both personal and social legacies that other forms of online communication cannot match. In this social context, the sharing of knowledge and creative ideas occurs and common meanings are developed through interactions (Edwards et al. 2011).

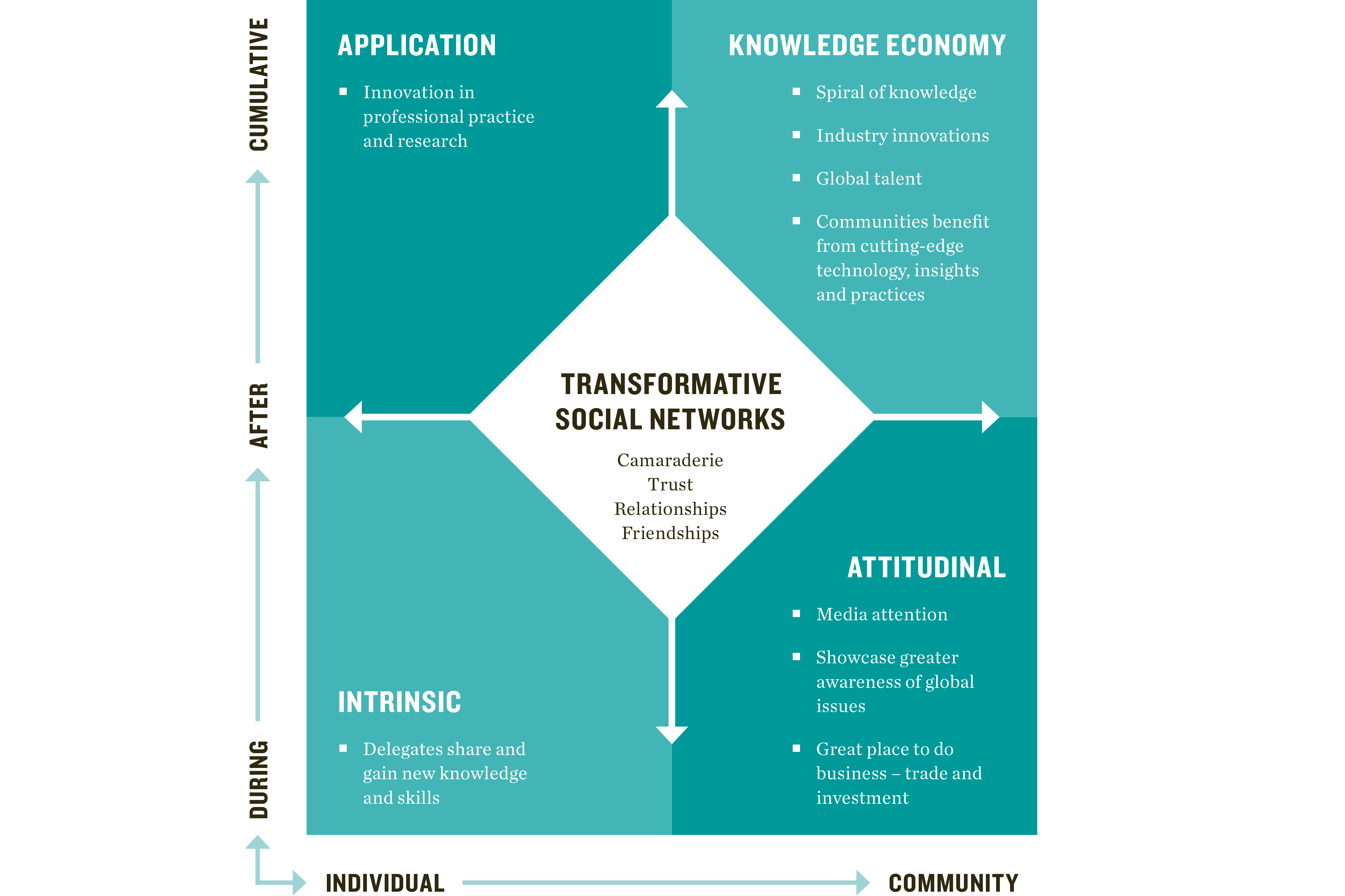

Diagram 1

Conferences – Long-term catalysts for thriving economies

Source: Foley, Edwards & Hergesell (2016)

Diagram 1 was developed as a result of our previous work, where we established that conferences are catalysts for thriving economies, with benefits accruing to individuals and communities immediately and over time. This latest research seeks to expand upon this conceptualisation by dramatically expanding the perceived time frame in which the outcomes of conferences are realised.

“Conference outcomes that reach fruition years and even decades after the conference is held”

To do this we decided to look backwards; to look back at conferences from the end of the long tail. We interviewed a range of people who had realised major achievements in their careers. We asked these people if and how their work had been influenced by conferences. What we explore through the stories in this book are the long tail legacies: the conference outcomes that reach fruition years and even decades after the conference is held. The HPV vaccine mentioned in the Introduction is an example of a long tail legacy. While conference research has established a comprehensive understanding of how legacies are facilitated by conferences over the short term, this book tells long tail stories from the field. We present the roles played by conferences in the diverse careers of influential innovators, researchers and thought leaders from across government, industry and academe in a wide range of fields.

Collecting the Stories

The stories presented in the book provide clear evidence of the ways in which conferences allow delegates to network, learn and innovate, and to co-create value as they forge new relationships and common agendas. Participants were selected from a diverse range of fields to represent the influence of a broad range of conferences (medicine, physics, applied science, agriculture, social policy). We looked for high achievers in each field (Nobel Prize recipients, industry and community leaders). We chose people who had attended their first conference well before 2007, to ensure a suitably long tail of conference influence for the research for this book (conducted in 2017). A list of potential participants was drawn up and each was contacted by email and phone and asked to participate. Semi-structured interviews were conducted, recorded and transcribed with those who agreed (65 per cent). How to deliver these stories was an issue we needed to consider. If we structured the stories for one type of audience would we alienate another? The stories were so personal that we decided to keep them engaging and accessible.

Further secondary research was conducted to add to each case study. Interested readers will find a bibliography that provides further information and reading at the end of the book. The stories were then returned to participants for verification. A decision was made by the authors to deliver the stories in an informal tone rather than use academic language and style. We wanted these stories and an understanding of the power of conferences to be accessible, not just to academics and their students, but also to government, industry and the broader community. Stories of serendipity, innovation and driving social change are relevant to us all. The stories are presented in no particular order; rather, the authors invite the reader to start with whichever story is of most interest to them.

“The Power of Conferences – Stories of serendipity, innovation and driving social change” by Deborah Edwards, Carmel Foley and Cheryl Malone. UTS ePress, University of Technology Sydney. The excerpt is published with permission.